Study suggests improved remedies for a problem affecting millions of Americans

If you haven’t had knee surgery, you may have a friend or relative who has. But do you know anyone who has had an operation on their jaw? Although the temporomandibular joint is crucial to speaking, chewing and even breathing, treatments for TMJ disorders are far less common than those for the knee.

Why that’s the case – and what can be done to improve how modern medicine handles problems with these two vital body parts – was recently examined by biomedical engineering researchers at the University of California, Irvine and other institutions. The results of the team’s comparative analysis were just published in the journal Cell Reports Medicine.

The key message of the study is that while the knee and TMJ are both heavily used joints that are subject to cartilage afflictions, the knee orthopedics field enjoys considerably higher funding for research, a wider array of engineered tissues and joint replacement options, and overall higher quality treatments.

“A thoroughgoing research, funding and treatment ecosystem exists for the relief of osteoarthritis and other ailments of the knee, but a similar infrastructure for the temporomandibular joint is comparatively lacking,” said senior co-author Kyriacos A. Athanasiou, UCI Distinguished Professor of biomedical engineering. “Both joints are essential to a good quality of life, so we would like to see people suffering from TMJ disorders given the same range of options as others have with their knees.”

The knee and TMJ are among the most heavily used joints in the body, and both endure large forces. Light jogging can expose the knee to the equivalent of over four times the body’s weight, and the TMJ can experience a force equal to the body’s full weight when biting.

According to the study, about a quarter of adults suffer some sort of cartilage problem, with about 14 percent of U.S. adults afflicted with knee osteoarthritis. Data are not as clear for jaw ailments, but the TMJ Association estimates that a similar number of adults have issues with that joint.

Nonetheless, the researchers calculated a 2,000-fold higher frequency of total knee joint replacements compared to TMJ. In addition, the knee is the focus of six times as many peer-reviewed journal publications and a significantly larger number of federal grants.

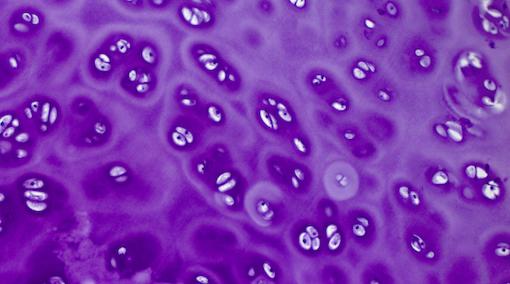

In a study in the journal Cell Reports Medicine, UCI biomedical engineering researchers discussed the similarities and differences between treatments for disorders of the knee and TMJ, suggesting ways to improve outcomes for people suffering from jaw pain. Chrisoula Skouritakis / UC Davis

In this and other studies, Athanasiou and his group have highlighted the existence of what they call the TMJ gender paradox, in which jaw disorders are four times more prevalent in women than men, and women present more severe symptoms.

“Unfortunately, this gender bias affects the field as a whole,” said co-lead author Benjamin Bielajew, a UCI Ph.D. candidate in biomedical engineering. “Studies have demonstrated that physicians are more likely to recommend pain medication to patients of their same gender. With most oral and maxillofacial surgeons being male, this could lead to women with TMJ disorders not getting the help they need.”

But gender isn’t the only factor behind differences in treatment. Although the knee and the TMJ share many similarities, their locations in the human body also influence how medicine approaches each, said co-lead author Ryan Donahue, a UCI Ph.D. candidate in biomedical engineering.

“The TMJ is situated right next to the inner ear, the brain and a complex network of sensory nerves, so naturally any surgical procedures are going to be that much more difficult. However, for the knee, you almost never see damage to surrounding nerves and other leg tissues because of knee surgeries,” Donahue said.

One example the researchers highlighted was a Teflon implant that was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in the early 1980s.

“It’s one thing for a Teflon surface to deteriorate and distribute particles around the hip joint, but when this happened with the TMJ, near patients’ brains, it led to catastrophic outcomes,” said co-lead author Gabriela Espinosa, a UCI postdoctoral fellow in biomedical engineering. “This resulted in the TMJ field being set back decades when compared to the knee; progress has been stifled even to this day.”

But that was decades ago, and now there are more advanced, naturally inspired engineered tissues that can be used to regenerate worn cartilage in joints throughout the body, including the TMJ, although the latter is only in the development stages at UCI and elsewhere.

“There have been enormous strides in regenerative tissue engineering solutions for the knee in recent years,” Athanasiou said. “Our hope is that success in regenerative medicine for the knee can be used as a template for similar long-term remedies for the TMJ.”

Bielejew said a more equitable approach toward TMJ is also needed for animal studies, clinical trials and patient treatment.

This study, which received funding from the National Institutes of Health, also included researchers and clinicians from the University of Texas School of Dentistry in Houston, Harvard Medical School, UC Davis, and private practice.

This story was originally published by the University of California, Irvine