Highlights:

- More pets may be getting sick from their owners than scientists have previously known.

- Every individual infection increases the odds that a mutation occurs and creates a reverse zoonosis: an infectious disease that jumps from humans to animals. For this reason, scientists recommend minimizing disease transmission among humans to reduce the risk of reverse zoonoses.

- Influenza and coronaviruses make up the majority of reverse zoonoses cases among pets. These viruses are especially apt to mutate because their genetic material is stored in RNA, which is prone to errors when replicated.

- Mammalian pets are more genetically similar to humans than reptiles, birds or fish — this makes them more likely to catch some diseases from their owners.

- In addition to directly impacting household pets, reverse zoonoses can also contribute to the spread of disease among livestock and wildlife, which increases the chances that future zoonotic disease outbreaks among humans might occur.

For as long as humans have been domesticating animals, there have been zoonoses, also known as infectious diseases that jump from animals to humans. Recent public health stories about COVID-19, avian flu and swine flu have thrust zoonoses back into the spotlight, sparking conversations about how animals like pets, rodents, birds or livestock might make humans sick.

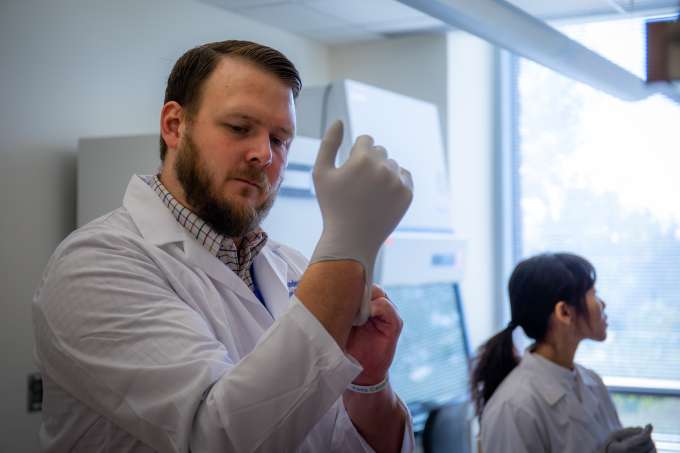

But people should also pay attention to disease transmission in the opposite direction, said Benjamin Anderson, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the University of Florida’s College of Public Health and Health Professions and member of the Emerging Pathogens Institute. Anderson is also a member of the UF One Health Center of Excellence. In June 2023, he and his colleagues published a comprehensive review of studies documenting instances of reverse zoonosis, or human-to-animal disease transmission, involving viral, bacterial, fungal and parasitic pathogens. The paper warned that pets, which share beds, kisses, snuggles and dining areas with humans, are at risk of catching diseases from their owners.

“We’re starting to see a lot of examples of reverse zoonosis. Pets are more susceptible than, maybe, we previously thought,” Anderson said.

What are reverse zoonosis?

Differences in the biology of animals and humans usually make it difficult for infectious diseases to spread between species. Viruses, for example, must bind to specific cell receptors in the host to reproduce and continue their life cycle.

“Typically, the viruses that I will have as a human are not going to fit into the receptors that a dog or cat has,” Anderson explained.

Because of the genetic diversity that a viral population might have, there will be different strains with varying levels of success at fighting off the host’s immune system and entering the host’s cells. Those varieties that can reproduce more will become more prevalent over time.

There is also the possibility of a virus developing a mutation that, by chance, allows it to fit in a new receptor and cross the species barrier. The risk of this happening increases every time the virus is transmitted and replicates in the presence of both humans and animals, leaving homes with pets especially vulnerable. Minimizing transmission is important, Anderson said, because every individual infection increases the odds that a mutation occurs, and a new viral strain emerges.

Still, reverse zoonosis gets little attention from researchers and popular media. This is partially because it is much easier to instead track instances where pets get their owners sick.

“When you see a human in the clinic, you can ask questions like whether they were around any animals, or if any of their pets were sick. But when you get an animal that’s sick, you may not always be able to get that kind of information to link it back to a human case,” Anderson said.

What kinds of reverse zoonosis already exist?

But just because people aren’t paying attention to reverse zoonosis doesn’t mean that it isn’t happening. The largest impact comes from influenza and coronaviruses, which are apt to mutate because their genetic material is stored in RNA, essentially the one-stranded version of DNA. The enzyme that checks for errors in RNA duplication is not as good as DNA proofreading enzymes — as a result, RNA viruses have a higher error rate and more frequent mutations. This is why so many influenza and coronavirus strains exist; this also makes these viruses likely candidates for transmitting diseases across species.

Anderson’s paper described several diseases that have been transmitted from humans to their pets, including the swine flu, human norovirus, dengue, COVID-19 and tuberculosis, as well as several lesser-known viral, fungal, parasitic and bacterial infections. While the vast majority of cases involved dogs and cats, there were also a few transmissions documented among horses, ferrets and parrots.

Not all pets face the same risk of reverse zoonosis. Mammals are more likely than birds or reptiles to get sick from their owners because they share more genetic similarities with humans. This means viruses will not have to mutate as much to cross the species barrier. The receptors in an animal’s cells are sometimes dictated by whether the animal is from a mammal, reptile or avian species. For example, the ACE2 receptor, which the virus that causes COVID-19 binds to, exists with minor variations in all mammals.

What are the impacts of reverse zoonosis?

In addition to being a health risk for cherished pets, reverse zoonosis can also later impact humans by contributing to the spread of a disease. Most seasonal flu viruses bind to a cell receptor that is found in humans and pigs and also exists in a slightly different configuration in birds. This unique circumstance of biology allows pigs to be infected by both human and avian influenza viruses at the same time. When that happens, pigs can sometimes serve as a mixing reservoir and produce new viruses that can cause pandemics.

Domestic animals like pigs can also sustain a pathogen population and become amplifying reservoirs. In 2016, Anderson co-authored a paper studying the spread of influenza viruses among people who worked in the swine industry. During the 2009 to 2010 and 2010 to 2011 flu seasons, when the 2009 pandemic influenza virus was circulating, cases peaked earlier in counties with more pig production. Researchers believe that the flu virus was circulating within pigs, creating an opening for outbreaks in the human population.

“We have to first ask how the pathogen gets into those animals in the first place,” Anderson said. “The pathogen doesn’t develop out of thin air in animals before suddenly spilling over into humans. While pathogens certainly can move from animals to other animals and can be picked up from the environment, exposures to humans also plays an important role. It’s this constant back and forth exchange that happens over time, increasing the probability of a mutation taking place that allows the pathogen to infect a new host.”

Tracking zoonotic transmission can be difficult because pathogens don’t always cause symptoms upon infection, and diagnostic testing even among symptomatic cases is often limited. This means movement of a disease between species can occur without anyone realizing. But regardless of whether an animal is sick, as long as it carries a pathogen, it increases the disease’s overall movement in an environment — putting the health of other living beings at risk.

What can we do to fight reverse zoonosis?

To help control zoonotic and reverse zoonotic transmission, Anderson recommended that people who are sick be more cautious around their pets, particularly if they know they have COVID or the flu. This does not have to mean a total quarantine, since being separated from their companion animals is not always possible or preferred.

Strong human-animal bonds also come with a score of benefits for emotional and mental well-being that should not be discounted. Anderson said that owners can still make a meaningful difference by limiting petting and keeping bodily fluids away from pets while sick. On a day-to-day level, people can also limit the spread of disease by feeding pets a healthy diet, providing fresh drinking water, keeping a clean living area and following a recommended vaccination schedule.

On the systemic level, more integrated research can also reduce the impact of reverse zoonoses. This means not just focusing on human health data to understand a disease, but also incorporating animal surveillance as well. “We have the diagnostic tools to track many different pathogens in both human and veterinary medicine, but not always the resources to see them used as broadly as is necessary to understand all of the epidemiological trends. In particular, we need greater testing among animals.” Anderson said. That kind of data could support pandemic preparedness by giving scientists important information about the movement of pathogens.

“I think it’s important to know not just about the human health issues, but also have a more complete picture as to what’s actually happening out in the environment,” Anderson said.

This story was originally published by the University of Florida on January 11, 2024.