When Jason Jurjevich and his husband Charles Walker went to close on a house a mile from campus in fall 2021, they expected plenty of paperwork.

But they were shocked to see the racist, antiquated documents they were required to sign before they could get the keys.

The home's chain of title included covenants – agreements or terms written into housing deeds – that explicitly barred people who are Asian or Black from living in the subdivision, unless they were servants to white homeowners. Such covenants, reminders of American housing discrimination, are still found in property records across the country, though they have been unenforceable since 1948 and illegal since 1968.

Jurjevich, an assistant professor in the School of Geography, Development and the Environment in the UArizona College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, learned of the covenants on his home when his realtor, a close friend, pointed them out as a courtesy. Despite the racist language, they would need to be signed to close the sale. Walker, who is the diversity and inclusion coordinator for the College of Applied Science and Technology, is Black.

With no other recourse, Jurjevich and Walker signed the documents. But by the next day, they were already thinking about solutions.

"It illuminated a set of questions for me as a researcher," Jurjevich said, adding that Walker then asked him what he could do as a geographer. "I said, 'I'm going to make a map.'"

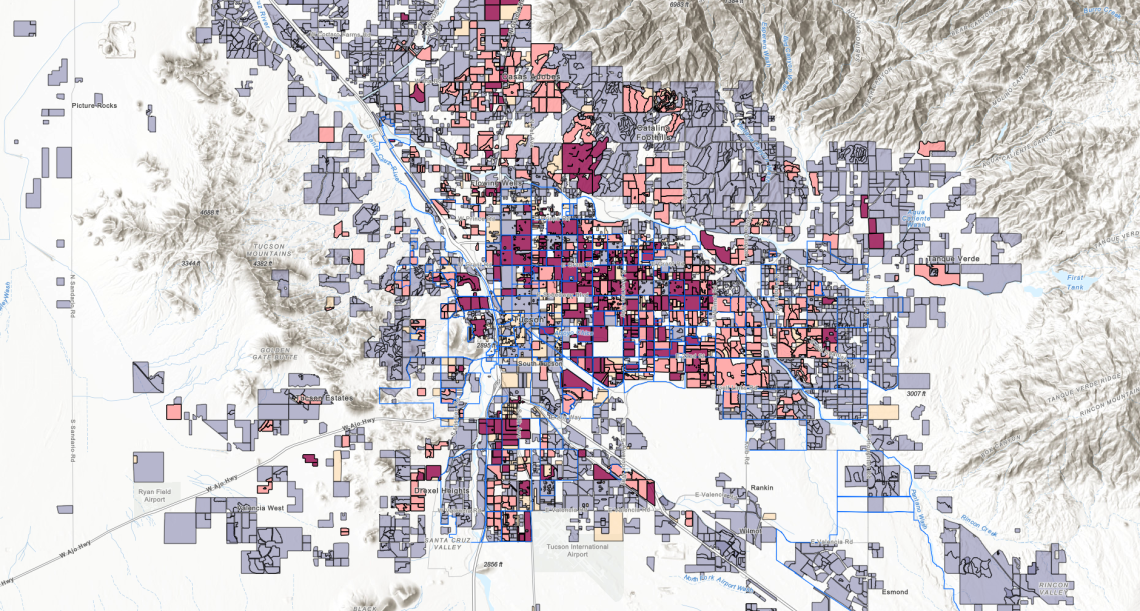

Nearly three years after Jurjevich and Walker's experience buying their house, Mapping Racist Covenants, which launched last year, has become much more than an interactive map showing all racist covenants in Pima County. Visitors can also learn where the covenants have been removed, and they can view the deeds as they were recorded, some more than a century ago.

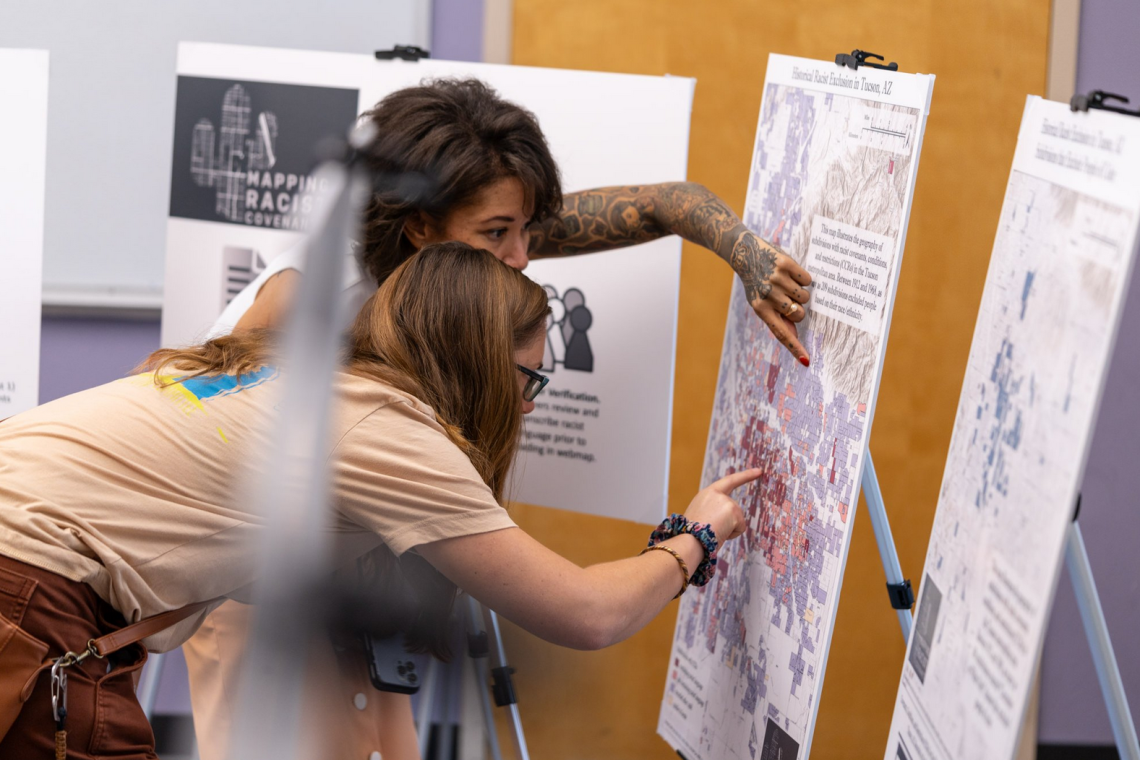

The project also has been the focus of community forums on Tucson housing policy.

"We as a community members need to be part of a conversation that talks about the history of racist covenants as part of a larger legacy of housing discrimination that affects and denies opportunities for people of color and other marginalized communities," Jurjevich said. "One of our goals was to start that community conversation."

The project has had clear civic impact, too: In late March, Gov. Katie Hobbs signed Senate Bill 1432, which allows homeowners to remove unlawful restrictions, such as racist covenants, from their housing deeds and other property records. Jurjevich took inquiries from state legislative staffers during the bill's drafting process and shared his team's research data.

How racist covenants proliferated and endured

Racist covenants were once central to housing discrimination in the United States.

A 1917 U.S. Supreme Court decision made it illegal for cities to create ordinances barring homeowners based on race. But neighborhood associations and other private owners, not bound by the same regulations, created the covenants as the next legal mechanism to keep neighborhoods segregated.

They proliferated across the U.S., including in Tucson. Jurjevich and his team found racist covenants in deeds for most of Tucson's housing subdivisions in the years after the 1917 Supreme Court decision.

The language in the covenants is explicit.

A collection of blocks in the Sam Hughes neighborhood, just east of campus, lists a 1925 covenant that once prevented the sale, rental or lease of homes "to any person of African or Asiatic descent, or to any person not of the White or Caucasian race." Housing deeds in one stretch of the Catalina Foothills still carry a 1930 covenant preventing sales, rentals and leases "to any person of Negro or Mongolian descent, or to any person not of the White or Caucasian race."

In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that a city's enforcement of the covenants was unlawful under the U.S. Constitution. In 1968, the federal Fair Housing Act made the covenants outright illegal.

Nearly 60 years later, 1 in 3 Tucsonans still live on a property with a deed that includes a racist covenant, according to the research by Jurjevich and his team.

Historically, many subdivisions could modify any covenant so long as 75% of their residents supported the change. But racist covenants were the exception – a perpetuity clause that came with most of them mandated that they remain as written forever.

The new state law makes it easier for homeowners, homeowners associations and other neighborhood groups to work around these perpetuity clauses and modify the deed language, Jurjevich said.

Building a 'community record'

Jurjevich led a team of two other faculty members and two students to build the Mapping Racist Covenants project:

- Arden Holloway, an undergraduate student studying urban and regional planning, collected and verified data on the covenants and helped organize community events around the project.

- Christine Kollen, librarian emerita in University Libraries who had years previously studied racist covenants, collected data about the covenants from county records.

- Yoga Korgaonkar, assistant professor of practice in the School of Geography, Development and the Environment, developed software to identify racist language in housing deeds.

- Liz Wilshin, a graduate student studying geography, managed public records requests to the Pima County Recorder's Office and verified the records.

The team first needed a list of properties that had been developed in between 1912 and 1968, the years when racist covenants swept across American cities before being made illegal.