What first comes to mind when you picture a healthy lifestyle? Many of us tend to focus on what we eat and how active we are. But an oft-neglected part of the picture is not just what we do, but when we do it. Establishing a regular sleeping and eating schedule can improve health in as little as one week. Two experts in sleep and metabolism explain why

Keeping Time

The answer has to do with the circadian clock: an internal biological 24-hour clock that’s present throughout the human body, in every cell. “The circadian clock machinery evolved to help your body anticipate what’s going to happen,” says Amandine Chaix, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Nutrition & Integrative Physiology at the University of Utah College of Health.

Chaix researches the connection between our internal clock and metabolism, or how we take in and use energy from food. Maintaining good metabolic health reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and many other serious health conditions.

A well-functioning clock helps our bodies prepare for daily life by tweaking our metabolism based on the time of day, Chaix explains.

At night, for example, the clock preemptively routes energy toward consolidating memories and detoxifying the body, which happen most while we sleep. When we wake up in the morning, the clock revs up our metabolism to prepare to eat and be active. Light exposure during the day—and darkness at night—keep the clock running in time with the outside world.

When You Eat Matters

This means that the exact same meal can impact your body differently, depending on what time of day you eat. Shortly after waking, the body is prepared to digest food with peak efficiency, thanks to increased responsiveness to the blood sugar-lowering hormone insulin. “Even if you have a massive amount of carbohydrates, the way your body’s going to metabolize it is very efficient because it is the right time of day to do it,” Chaix says. In other words, a big breakfast won’t cause the same spike in blood sugar as the same meal eaten later in the day.

On the other hand, eating late at night can be especially unhealthy. Lots of energy is allocated to the brain and the liver at night, to maintain the body processes that happen during sleep. An unexpected midnight snack forces the body to suddenly reroute energy to the digestive system, striking an uncomfortable compromise between digestion and sleep-related processes.

The Importance of a Sleep Schedule

But lack of sleep can disrupt the clock, which in turn disrupts metabolism, warns Christopher Depner, PhD, assistant professor in the College of Health’s Department of Health & Kinesiology. When you don’t get enough sleep, you’re often also exposed to lots of electronic light late at night, which makes the clock try to reset to match the light cycle. “It’s like you’re inducing jet lag continually,” Depner says.

And that jet lag has rapid health consequences. Depner’s research has found that sleep-deprived people are more likely to eat more—and eat late at night, which can noticeably decrease insulin sensitivity in less than a week. “We can take people from healthy to a level of insulin sensitivity that would almost be prediabetic in as short as five days,” Depner says. “It’s really scary.”

It takes about a week of sufficient sleep to reverse the metabolic changes, he adds—sleeping in on weekends isn’t enough.

Eating late at night can also affect the internal clock of the digestive system, potentially knocking it out of sync with the light-based clock found in the brain. Ideally, eating breakfast shortly after you wake up keeps your digestive system synchronized with your brain.

However, “If the food comes when it’s not supposed to, then the digestive system is running on a time that’s different from the brain,” Chaix says. “It’s like having your brain in Boston and your guts in San Diego.” Long-term misalignment can weaken the clock as a whole, making it harder to fall asleep and harder to wake up, Chaix says.

How to Set Your Clock

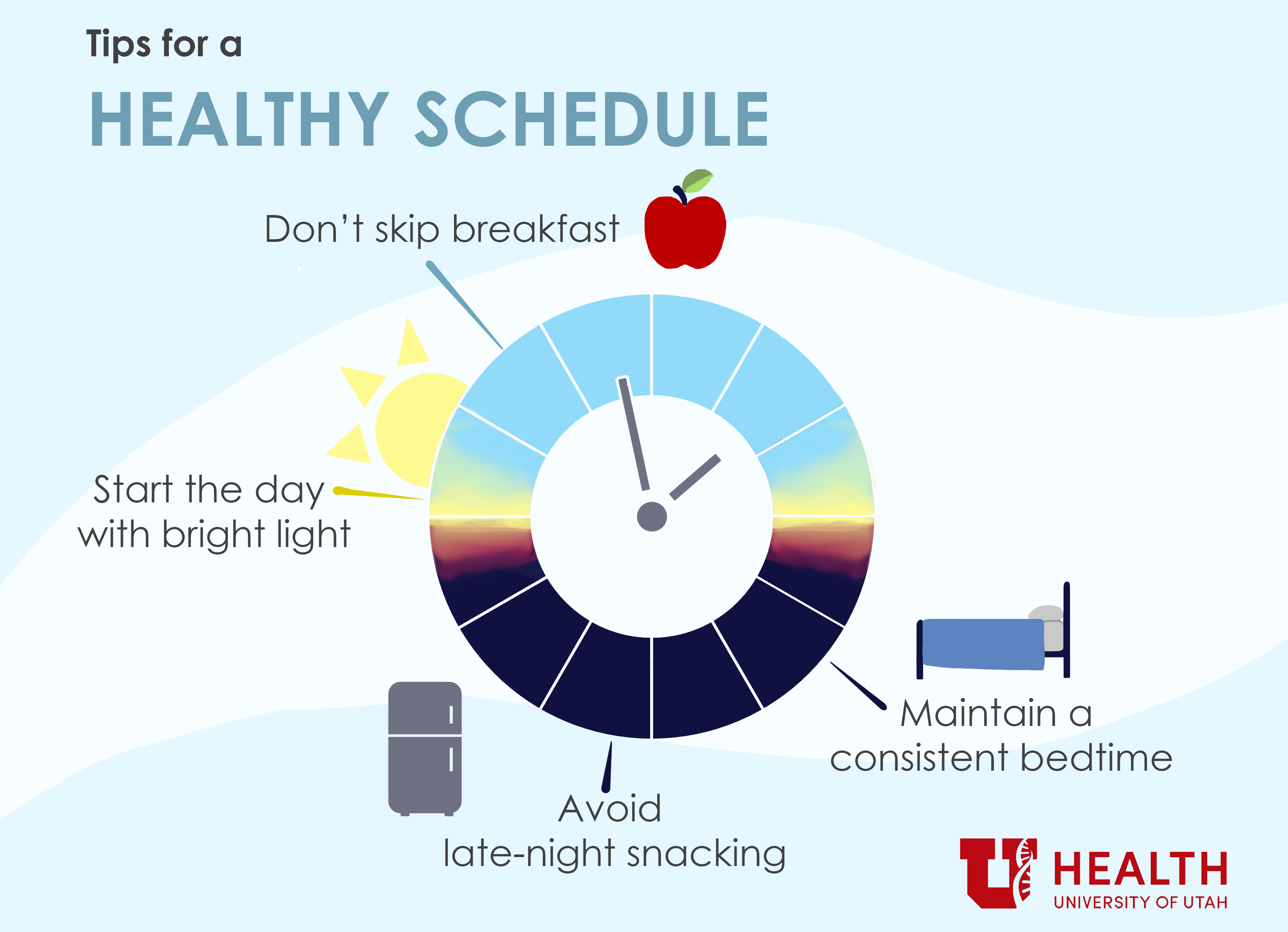

Getting enough sleep and keeping a consistent schedule are often difficult—and sometimes impossible. But small steps can help strengthen the circadian clock and improve health even in tough circumstances.

“Even if you’re not able to get enough sleep, other strategies can help mitigate some of the health consequences,” Depner says. Because bright light sets the brain’s circadian clock, starting your day with plenty of light exposure can help, Depner says, as can avoiding bright electronic light late in the evening. He’s currently testing ways to improve clock function and sleep health in people with chronic poor sleep.

Chaix adds that maintaining a regular schedule can be beneficial, even for people who work or are active at night. “Consistency is the key,” she says. “Whatever rhythm you have, stick to it so that your clock can adapt and predict that cycle, even if it’s not the cycle that’s completely the same as the sun.” Part of her current research aims to help figure out the healthiest times to eat for people who work night shifts.

While recalibrating one’s schedule may seem like a big task, Chaix adds, even small adjustments can help. “It doesn’t have to be that tomorrow you wake up and you implement all of these all at once,” she says. “There are little steps, and all of them are toward a mighty goal of improving health.”

This story was originally published by the University of Utah on June 25, 2024.