Reach of certified community behavioral health clinics reflects bipartisan support for investment in improving behavioral health

A decade after the establishment of the certified community behavioral health clinic (CCBHC) model, more than 60 percent of the US population has access to such facilities and the mental health and substance use disorder treatment services they provide, according to a new study led by researchers at the NYU School of Global Public Health. Moreover, these clinics are expanding the availability of crisis mental health services, including mobile crisis response teams and stabilization.

“Certified community behavioral health clinics have become a cornerstone of bipartisan strategies to increase access to and improve the quality of behavioral health care in the United States,” said Amanda Mauri, an assistant professor/faculty fellow at the NYU School of Global Public Health and the lead author of two new studies on CCBHCs.

A new approach to community-based behavioral health care

CCBHCs fulfill federal criteria related to providing outpatient mental health and substance use care, including crisis services, regardless of patients’ ability to pay. The federal government established the criteria for the CCBHC model in 2014, and the first CCBHCs opened in October 2016. Clinics that become CCBHCs are typically community mental health centers that offered outpatient behavioral health care before becoming CCBHCs, but other types of facilities—like hospitals and federally qualified health centers—are also receiving CCBHC designation.

“The creation of CCBHCs marks the first significant shift in federal involvement in community behavioral health care since the 1980s, when Congress converted the national community mental health center program to a block grant,” said Mauri. “Given this important policy change, it is essential to evaluate whether and in what ways CCBHCs change community behavioral health care, particularly for persons who are uninsured, underinsured, and enrolled in Medicaid.”

Over the past decade, federal funding for CCBHCs has increased—for instance, the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, which became law in 2022, funnels $8.5 billion over 10 years into CCBHCs. Clinics can become designated as CCBHCs through two initiatives: Medicaid programs that make bundled payments to clinics on a daily or monthly basis, or through the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Expansion Grant program.

Despite the significant investment in CCBHCs, there is little research on these clinics: where they are located, what services they provide, and who they reach. To address this gap, Mauri and her colleagues created a dataset of CCBHCs and began exploring their reach and services.

The wide reach of CCBHCs

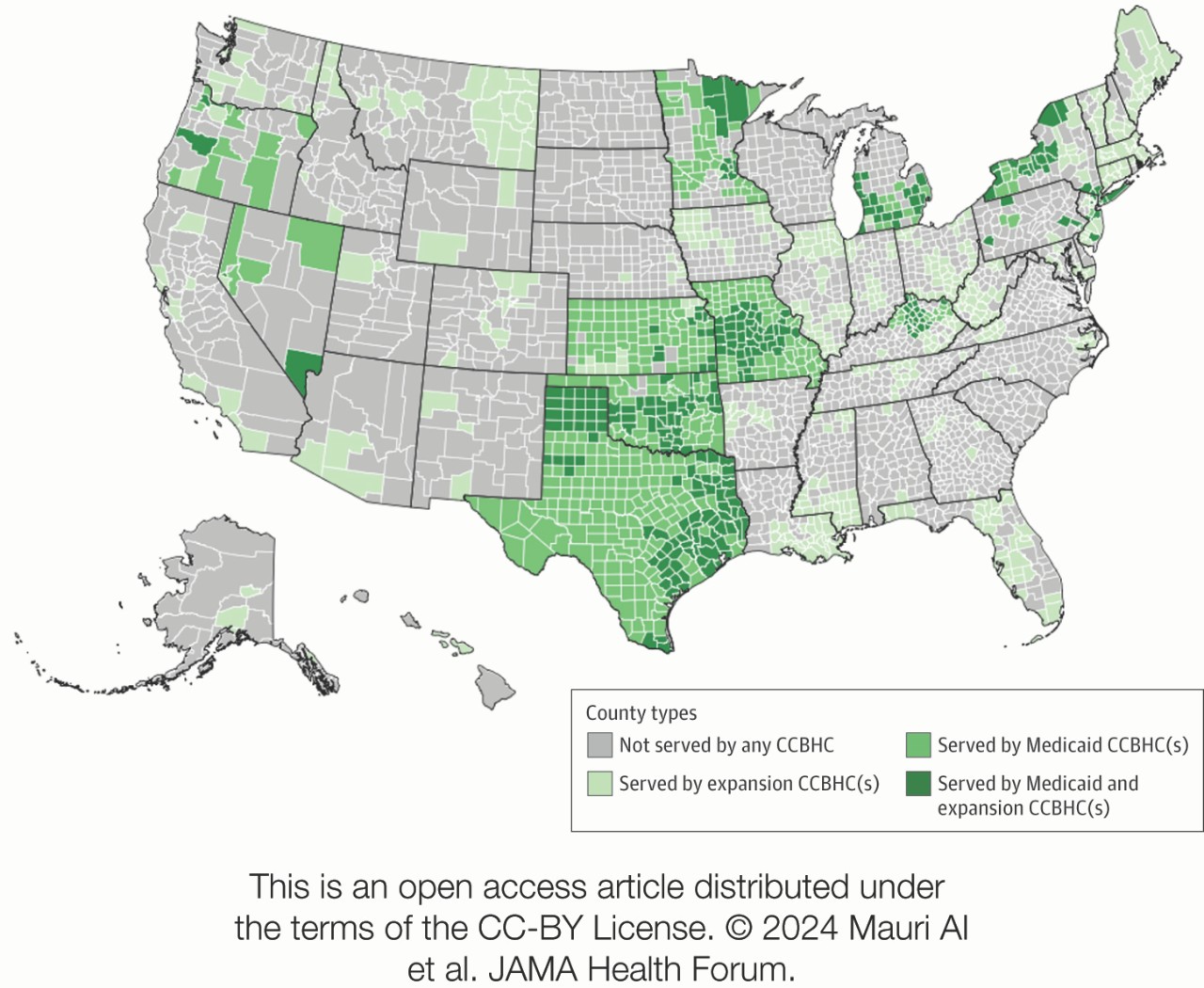

In a study published October 4 in JAMA Health Forum, the researchers found that CCBHCs have a wide-reaching network, with the proportion of US counties and people residing within a CCBHC service area substantially growing since the first clinics opened in 2016.

As of June 2024, 39.43 percent of counties are served by CCBHCs (22.85 percent of counties served by Medicaid CCBHCs and 25.37 percent of counties served by SAMHSA-funded Expansion CCBHCs, with some served by both). More than half of CCBHCs serve multiple counties. In addition, the majority of the US population—62.26 percent—have access to mental health care through local CCBHCs (26.63 percent by Medicaid CCBHCs and 53.93 percent by Expansion CCBHCs, with some served by both).

While the researchers found geographic differences in where CCBHCs are located, they note that these disparities do not necessarily fall along partisan lines. For instance, Texas was an early adopter of CCBHCs, establishing statewide access through a Medicaid program. In contrast, North Dakota, South Dakota, Delaware, and South Carolina had no CCBHCs as of June.

“This is one of the few policy spaces where there's bipartisan support—we're seeing Republican and Democratically controlled states alike launching CCBHC initiatives, and we’ve seen significant investments in the program under the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations,” said Mauri.

Increasing crisis services

CCBHCs are required to provide the three main types of behavioral health crisis care: 24/7 call lines, mobile crisis response, and crisis stabilization. The need for crisis services has grown since the 2022 launch of 988, the new national number for the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.

To better understand the crisis services provided, Mauri and her colleagues analyzed national survey data from the National Council for Mental Wellbeing on CCBHCs, along with the demographics and socioeconomics of the areas they serve. Their findings were recently published in the journal Psychiatric Services.

The research found that clinics receiving CCBHC Medicaid bundled payments had much higher odds of adding new crisis services when becoming CCBHCs than clinics not receiving these Medicaid payments.

“This suggests that the CCBHC Medicaid bundled payments matter and may be effective tools for increasing the availability of resource-intensive crisis care, like mobile crisis response and crisis stabilization services,” said Mauri.

The researchers also found that CCBHCs with higher staffing levels relative to the population they serve were more likely to directly provide crisis services, rather than contracting with third-party providers.

In addition to Mauri, study authors for the JAMA Health Forum study include Nuannuan Xiang of Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, Danielle Adams of the University of Missouri-Columbia, and Jonathan Purtle of the NYU School of Global Public Health; additional study authors for the Psychiatric Services article include Saba Rouhani and Jonathan Purtle of the NYU School of Global Public Health. The research was funded in part by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH121649).

This story was originally published by New York University on October 4, 2024.