The road winds deep into the mountains, past waterfall pit stops and scenic pullovers. Leaf peepers horde the edges of this narrow highway, trying to catch a motionless glimpse of the coppers, golds, and rust-reds that burst from the surrounding forest. It’s autumn in Highlands, North Carolina — and the trees are alight.

This small mountain town may be known for its stunning views and thriving art scene, but it’s also home to the Highlands Biological Station — a field site for the UNC Institute for the Environment that’s administered by Western Carolina University. Carolina undergraduates spend fall semester here each year to discover what research in the mountains looks likes.

Guest lecturers present at the station each week. Here, conservation biologist JJ Apodaca (center) leads a lesson on conservation genetics — a field that uses genetic knowledge to reduce the risk of extinction in threatened species. Today, he explains, they will search for salamanders.

North America has the highest phylogenetic diversity of salamanders on earth and this region of the Appalachian Mountains is home to about half the species in the United States. “The Appalachians are some of the oldest mountains in the world,” Apodaca says. “So salamander species have had a long time to evolve here.”

Some hypotheses suggest that the largest salamander family in the world — the Plethodontidae, or the lungless salamanders — evolved and diversified in the Appalachians. They account for about 66 percent of all salamander species, according to Apodaca. Part of this family, the Blue Ridge two-lined salamander (Eurycea wilderae) is one of the most common species found in the Great Smoky Mountains, residing in both forests and streams at an average of 1,200 meters above sea level.

Searching for salamanders is a little like finding a needle in haystack — but this needle has four legs that move incredibly fast. Collecting them requires patience and dexterity.

The largest stream salamanders in the southeast, blackbelly salamanders (Desmognathus quadramaculatus) average four to seven inches in length. Although they typically hide under rocks during the day and hunt at night, some will boldly rest out in the open. This student stares in awe at the biggest catch of the day.

Salamanders eat mostly invertebrates like flies and beetles, which survive on leaves, and the more leaves left unconsumed means less carbon released into the atmosphere. At common densities, salamanders send an average of 179 pounds of carbon into the soil versus the air — enough, according to scientists, to affect global climate.

Equipped with vernier calipers, students measure the length and width of each salamander’s snout, tail, and body. They also count costal grooves — the lateral indents along the salamander’s body that mark the position of the ribs. These little trenches increase the surface area of the skin for water absorption, helping it travel up the body via capillary action.

Each bag is packed with leaves to keep the temporary environment moist and safe — it gives the salamanders a place to hide, which lowers their stress levels. After making all their measurements, students release the amphibians back into the woods.

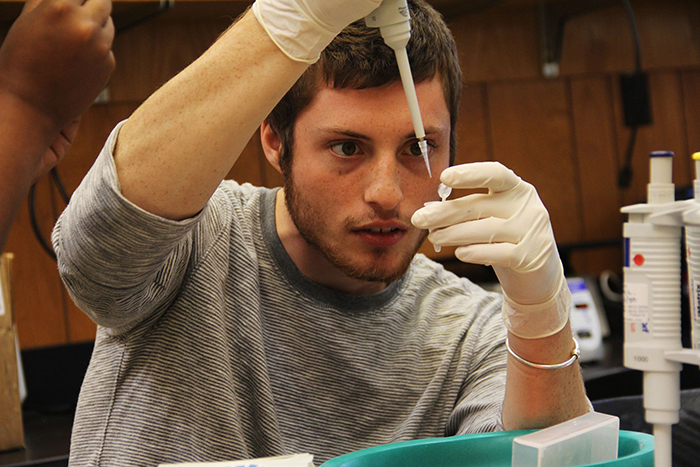

Back in the lab at the station, Apodaca explains how to analyze genetic samples using a procedure called polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which amplifies a specific sequence of DNA in a test tube.

For many students, this is their first time completing experiments in a lab. “It was very satisfying to conduct the PCR DNA analysis, receive the results, and be able to conclude something significant from it,” Elizabeth Monaghan (center) says. “For example, we learned that Hellbender salamanders only live in certain streams, which makes them more important for conservation practices.”

Each student walks away from the Highlands Biological Station with a new take on the world. “Every place has its own tapestry — though some might have more species, more interesting geological history, more complex land-use,” Forest Schweitzer, a senior majoring in environmental science, says. “Through studying these tapestries, we are better able to situate ourselves in the world we live in.”

JJ Apodaca is the associate executive director for the Amphibian and Reptile Conservancy.

Elizabeth Monaghan is a senior double-majoring in environmental sciences and biology within the UNC College of Arts & Sciences. She is also a lab assistant in the Center for Environmental Medicine, Asthma, and Lung Biology within the UNC School of Medicine.

Forest Schweitzer is a senior majoring in environmental studies within the UNC College of Arts and Sciences.

By Alyssa LaFaro

Hunting for Salamanders in the Highlands was originally published on the University of North Carolina's website.