Department Ownership of the Curriculum

One key to improving undergraduate STEM education is for a department and its faculty members to recognize and acknowledge their collective responsibility to improve the effectiveness of introductory/foundational courses. In a research university achieving such a departmental commitment is challenging both because many (sometimes most) of the students taking these introductory courses will not major in the department offering them and because the attractions and rewards of research universities for faculty members most often are in research and graduate education.

AAU has observed that departments most likely to emphasize evidence-based active-learning strategies in foundational courses have thought deeply about the curricula and content of these courses, along with ways to assess student learning in them. Ultimately, collective responsibility for shared learning objectives by course will necessitate developing a uniform vision of educational improvement among faculty members within and across departments, as well as the development of mechanisms to assess progress in teaching effectiveness for all students.

Consider the Biology Initiative at MSU as an example of this process. The Biology Initiative focused on introductory genetics, which serves three colleges and 18 majors. No single college or department “owned” the course, which made it difficult to assign teachers, develop common learning objectives, and assess results. Funded by the Provost and coordinated with the AAU project at MSU, the first step in this reform initiative was to create a management committee. The committee, which reported to the Dean of Natural Sciences, was responsible for introductory genetics, including the assignment of instructors and the development a set of common learning objectives. This arrangement increased cross-department communication and led to more coordinated instructional and assessment practices. Follow-up assessment showed a substantial increase in student performance relative to the prior format of introductory genetics.

As another example, at UC Davis, the Colleges of Bioscience, Agriculture, and Environmental Science, as well as the Department of Chemistry, recently developed a shared five-course sequence for students in the Life Sciences (piloted in Fall 2017 with the initial work on three-quarters). This collaboration represents the first time that such a diverse group of faculty members and departments cooperated to develop new courses and a course sequence. UC Davis then linked its summer bridge program with the new curricular sequence and identified discrete paths for students to take chemistry courses based on their interests and intended majors.

Since the start of the AAU project, UNC-Chapel Hill has transformed all of its introductory courses in Biological Sciences in a manner consistent with evidence-based pedagogies. Physics as a department opted to reform all introductory courses in a similar manner. One key: Regardless of the instructor there will be common materials and examinations in these introductory courses.

Among the most visible evidence of departmental ownership of courses and curricular is at Brown. The project initially was housed in the Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning with the Director playing a lead role in the project. When the Director unexpectedly left, the chairs in key STEM departments took responsibility for the project and made sure that the departments took responsibility for course and curriculum improvements.

Institutional Commitment to Long-term STEM Reforms

Institutionalizing reforms of undergraduate STEM education at research universities eventually requires internal institutional investment of resources; it cannot be achieved solely by a series of externally-funded grants. The nature of this investment can vary, supporting personnel, infrastructure, and/or space. Public pronouncements of support by university leaders are also important contributions to the spread of instructional reforms across departments.

Each of the eight project sites has garnered institutional support for long-term STEM undergraduate reforms. At Brown, the Office of the Provost has continued its pledge of budgetary support for the project despite turnover in that position. The Provost and dean have committed institutional resources to assist participating departments in reforming introductory STEM courses (including hiring and training Teaching Assistants). In addition to financial resources, the central administration has made public pronouncements in support of the AAU STEM reforms and has engaged with project activities. Brown also has modified some teaching spaces to better reflect the use of active learning techniques. The most significant long-term commitment, however, is signified by the hiring of a specialist, working in the Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, who will help train problem-solving group facilitators. This move by the university is part of an emerging project to sustain and strengthen the culture of problem-solving created by the AAU project. The project is a large-scale, joint effort between the Sheridan Center, the Office of the Dean of the College, and the STEM department chairs and faculty.

At MSU, the Provost, deans, and chairs have made efforts to encourage academic programs to hire individuals knowledgeable about evidence-based teaching. Chemistry hired an individual whose sole job focus is to support curriculum transformation. Also in Chemistry, the Provost provided funds for undergraduate learning assistants (ULAs) and is funding the alteration of classroom space. The Provost funded new graduate and undergraduate teaching assistants for introductory biology courses. Three new course curriculum coordinators were hired with university funds; their focus is on the introductory sequence in biology. Physics hired several ULAs for teaching introductory courses.

At UPenn, one key to increasing the number of faculty involved and institutional support has been the evidence of success—students taking reformed courses achieve better than those taking traditional courses and seem to persist in STEM as well (the evidence of this outperformance is especially strong in bioengineering and physics). The evidence of improved student performance has led faculty and chairs to vote to sustain the SAIL classroom reform model. UPenn has also received central administrative support for building new classrooms that fit active learning instructional strategies.

Despite substantial institutional budgetary constraints, UA received a pledge to continue funding of the core faculty learning community and workshop efforts. UA leaders have also contributed resources to reform classrooms and provide salary for some teaching-related positions. Central administrators also have regularly reported on the AAU project achievements in campus news outlets. UA commitment of resources to long-term reforms include funds for a new Center for University Educational Scholarship (including a director and three fellows).

Extensive turnover by senior university leadership at CU Boulder in recent years, makes it difficult to assess the stability of long-term commitments to reform by central administration. However, CU Boulder received institutional funds for three new STEM teaching-oriented faculty hires and the central administration now requires departments to answer three questions about its effectiveness. This signals that the central administration is cooperating with AAU project goals.

The central administration and various colleges at UC Davis now contribute funds to support the STEM reforms started by the AAU project. For example, the Colleges of Biology and Agriculture now support the continued reform of Chemistry III. The Provost now commits money for the CEE, multiple faculty learning communities, an evidence-based course redesign institute, and course design awards.

UNC-Chapel Hill provides an example of the investment of resources at the precise time needed to expand reforms: The Provost and several Deans agreed to contribute university funding to continue the course buy-out strategy (i.e., both mentors and apprentices get a full course credit for co-teaching one course) after AAU funds disappeared, which enabled UNC-Chapel Hill to expand the numbers of participants in its STEM reform programs. Beyond its support for the original AAU grant, UNC-Chapel Hill central administration now supports salaries for five STEM instructors experienced in Discipline-Based Education Research (DBER) and evidence-based teaching, the Chancellors Scholars program (for minority students), summer teaching institutes for faculty members, and classroom renovations. In addition, the Quality Enhancement Program (QEP) at UNC-Chapel Hill has been funded until at least 2022. The QEP will take over the work started by the AAU project after funding ends.

The substantial resource commitment to CIRCLE is indicative of an institutional commitment to the overall reform of STEM education at WashU. CIRCLE recently obtained a four-year commitment to support its new Transformational Initiative for Education in STEM (TIES), which is adapted from Carl Wieman’s Science Education Initiative. The Chemistry Department has also funded a permanent position to disseminate and institutionalize educational reforms in that department.

Leveraging Other Undergraduate Reforms on Campus

Project sites successfully leveraged existing undergraduate reform efforts in their efforts to broaden the reform of STEM education. Taking advantage of resources already committed to other types of educational reforms, either from external grants or from internal sources, was a common theme. MSU was able to leverage various ongoing projects to create a larger, more visible, and longer-lasting presence on campus.

Better coordination of various administrative units responsible for undergraduate education also was evident. Successful forms of coordination included linking advising and co-curricular units with classroom instruction as well as consolidating units to form a more effective organization. UC Davis is a prime example of the latter. UC Davis has given greater visibility to educational reform efforts on campus by merging the iAMSTEM Center with the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning (CETL) to form the Center for Educational Effectiveness (CEE) and providing funds for CEE staff. CEE is now supported with regular university funds and works with Student Affairs Administration (SAA) to combine non-curricular information about students with classroom data to better identify factors in student success.

Linking STEM educational reforms with university initiatives also proved successful. As a prime example, at UNC-Chapel Hill, the Chancellor’s Strategic Framework now requires all 13 schools and their departments to show evidence of high impact research and innovative teaching. The Quality Enhancement Program (QEP) promoted by central administration includes a focus on improving undergraduate STEM education. The UNC-Chapel Hill project also has emphasized the improvement of academic performance and degree retention among underrepresented minorities, which is a university priority.

Demonstrating more effective ways to measure the quality of teaching also has been used to support institutional and state-wide efforts to improve teaching. As an example, at UA, the AAU project has taken advantage of university resources for improving teaching and learning, incorporating activities and staff into an overall STEM reform movement. Two additional NSF grants have supported an expansion of AAU project-initiated efforts. Finally, the UA team has cited state-level policy emphasizing the quality of education on public campuses to promote STEM reforms at UA.

All project sites were able to leverage the reputation of AAU in extending the visibility of their projects. Also, membership in other national networks enabled project sites to leverage external support for local reforms.

Institutional Commitment to Align Faculty Rewards to Evidence-based Teaching Practices

A primary goal of this initiative was to bring about a shift in the culture of research universities to increase the use and valuing of evidence-based instruction to the point where it became the norm rather than the province of a dedicated few. AAU was aware that mainstreaming evidence-based pedagogy would require aligning the faculty reward structure with (often) new expectations for teaching, realigning rewards to reinforce an expectation for teaching excellence consistent with the use of evidence-based instruction. Of all the project goals, changing faculty rewards to increase the value of teaching has been the most difficult. Despite AAU’s expectation as expressed in the proposal process, only two of the eight project sites proposed actual plans to work on the routines by which their campus normally addressed merit, promotion, and tenure judgments, including taking this up with the political entities, like faculty senates, that would have to be on board for widespread change to occur.

In spite of this lack of emphasis by projects on and the apparent resistance to systematically address this aspect of culture change, AAU saw clear trends over the years toward aligning the institutional incentive structure with support of evidence-based teaching. For example, Physics at MSU now requires every pre-tenured faculty member to have at least one formal observation by a trained professional (in evidenced-based teaching) each semester. Tenured faculty members must do so at least once per year. These findings are now an official part of the faculty dossier in Physics. CU Boulder reformed its institutional requirements for departmental and faculty performance to include excellence in teaching. At WashU, for promotion and tenure, the Schools of Arts and Science and Engineering and Applied Science now require faculty members submitting materials for performance review to include details about their teaching and participation in professional development activities (teaching certificates from CIRCLE are helpful in this regard). In the past, only student course ratings were required for faculty review. At UA the promotion and tenure process at the university level has been modified to include a required teaching portfolio and peer assessment/observation of classroom instruction. In the future as part of its regional accreditation and monitoring by The University of Arizona higher learning commission, UA will gather data on the use of evidence-based teaching and the quality of instruction. UNC-Chapel Hill similarly will gather data on teaching and learning as part of its regional accreditation.

AAU used two data sets for drawing more general inferences about the place of evaluation and assessment of teaching in judging faculty for merit, promotion, and tenure. As noted above, information about this was requested in the annual reports. Second, in each of the two rounds of common data collection across the sites (2014 and 2016), this issue was addressed in two ways. The survey included questions that elicited faculty perception of how this work is valued by their department and institution.

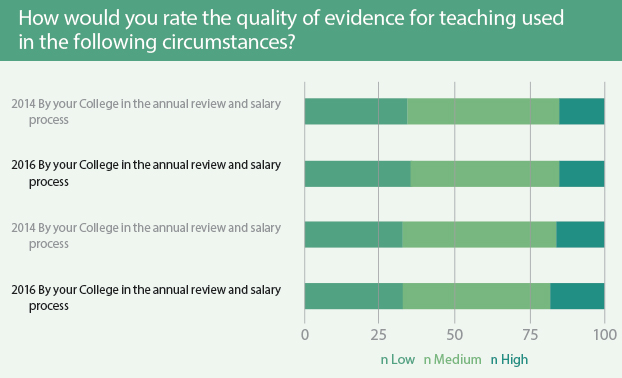

- Perceptions of recognition of the importance of teaching by departmental and campus administrators (>3.0) out of sync with perceptions of the role effective teaching plays in annual review and salary (≈2.5).

- Most felt the quality of evidence for teaching used was of low (about 33%) or medium (about 50%). Only about 15% judged the quality high.

The heads of participating departments were asked to write brief statements about how teaching is evaluated and valued in their department. In 2014, 30 department chairs from seven of eight institutions responded. In 2016, 30 department chairs from eight institutions responded. In both years, respondents asserted that teaching is highly valued. Many of them quoted university level or college level language to this effect. Most provided some level of detail about their process for collecting information and providing feedback to faculty.

Student evaluations at the end of courses were overwhelmingly the metric used in 2014. Faculty personal statements, review of course materials, and observation also played some role, especially in tenure decisions. It was not possible to tell from most of the department head statements whether these additional criteria made any explicit address to use of evidence-based instructional methods. In 2016, student evaluations were still the major metric, but there were two statements that could be taken as critiques of their usefulness. One of these is mild – a chemistry department notes that “scores will be considered, but not weighted heavily unless they are extraordinarily positive or negative.” The other is more robust – a mathematics department is engaged in a debate over whether to use them at all, given the literature on implicit bias and other confounding elements in their use.

By 2016 most departments mention some level of peer observation, but in only a few cases was it clear that observers would use tools that helped them go beyond their own experience. Many departments expect that tenure review will include a portfolio that contains representative course materials.

In 2016, twelve of the 30 made explicit reference to evidence-based pedagogy as an important criterion for tenure track faculty, and two more included it for non-tenure track faculty but not tenure track, as compared with six and two respectively out of 30 in 2014. Eight had statements classified as permissive, that is, allowing faculty to present use of evidence-based work without implying it is expected, compared to six in 2014. Binning the ranges shows that attention to this was evident in 73% of the responses in 2016, compared to 47% in 2014. Three among the ones noted above for 2016 specifically mentioned student outcomes as a criterion: one provided no detail, another tracks student success in later courses, and the third tracks assessment of achievement of learning goals that have been agreed by the department.

Between 2014 and 2016 there was a shift in the tone of the responses that, taken collectively, points to culture change, at the very least at the level of chairs being more willing to think beyond the cookbook answers to the presenting question. For example, there was more of a tendency for the chair to say or imply that keeping a focus on good teaching is an important part of the chair’s role. The statements from one institution (five departments) all emphasized, and took pride in, their use of the resources of their Teaching Center. Finally, some chairs took the question as an invitation to comment on culture change more generally and spoke of seminar presentations and an increase in department conversations about teaching, as well as named awards for teaching.

There were cases in which an aspect of the site’s AAU project plan was particularly evident in the response. These include CU Boulder’s beginning to introduce very explicit expectations of an effort to use evidence-based pedagogy in the merit review criteria; and UPenn Math Department’s very robust reexamination of the use of student ratings and alternative metrics, based on their experiments in introductory math. Another institution, on the other hand, presented a striking difference between the focus of the project leadership, which has tended to espouse the view that faculty motivation to change is intrinsic and not driven by the institutional reward system, and the responses from its chairs which also cite its Natural Sciences college-wide resources. The College policy is explicit in its criteria in a way that points to use of modern pedagogy as desirable.

In general, the trends observed in the department heads surveys are echoed in the annual reports from project leadership, although not perfectly, as noted above. It is useful to note that the last five years have seen the appearance of significant new tools for peer observation and self-analysis of teaching practice, so that it is easier now for a department that seeks alignment of incentives with good practice to begin to articulate what is needed. Examples of new approaches are presented in this section and in section 3, which come not only from a funded project site but several members of the larger AAU network.

One of the barriers to including information about teaching in tenure and promotion decisions is the lack of a scholarly approach to teaching evalu