LAWRENCE – The word “plumber” comes from the Latin word for the metal “lead.”

But lead coupled with pipes that transport drinking water makes a terrible combination … and one which resulted in the Flint water crisis, among other similar public health hazards.

“Lead is a neurotoxicant that builds up in the body over long-term exposure, with children especially vulnerable to its negative effects,” said David Slusky, a professor of economics at the University of Kansas.

“Too often, parents and care providers do not learn of such an exposure until a child receives a lead test showing elevated levels of lead in blood. Early-in-life lead testing together with remediation of potential lead contaminations allows early detection of exposure and prevents further harm.”

Slusky’s new article titled “Blood Lead Testing in Flint Before and After Water Contamination” reveals how, despite a highly publicized lead advisory, children in Flint, Michigan, who were enrolled in Medicaid received lead tests earlier but the proportion of Medicaid-eligible children who were tested did not change. His research advocates focusing on primary prevention to reduce lead exposure. It appears in Pediatrics.

Such exposure can introduce cardiovascular problems, high blood pressure and developmental impairment affecting sexual maturity and the nervous system. Evidence suggests eliminating lead pipes would yield benefits for generations.

Co-written by Derek Jenkins of Rice University, Daniel Grossman of West Virginia University and Shooshan Danagoulian of Wayne State University, Slusky’s study uses the complete set of Medicaid claims data for individuals born in Michigan between 2013 and 2015, linked to their birth record data containing maternal census block of residence during pregnancy. The data allowed the researchers to identify children who did not have any lead test claims. The resulting data set tracked 206,001 children.

“While the particular circumstances of this study are specific to Michigan, lead is present in homes across the nation, especially in older homes and cities with older infrastructure,” said Slusky, who also has an appointment in the Department of Population Health in the KU School of Medicine.

He explained that at the time of the Flint water crisis, an investigation found approximately 3,000 localities across the U.S. with lead poisoning rates more than double those in Flint. Although the benefits of lead testing are universal (and required for those enrolled in most Medicaid programs at ages 12 and 24 months), compliance is low. Nearly half of children on Medicaid have not received a test by age 13 months.

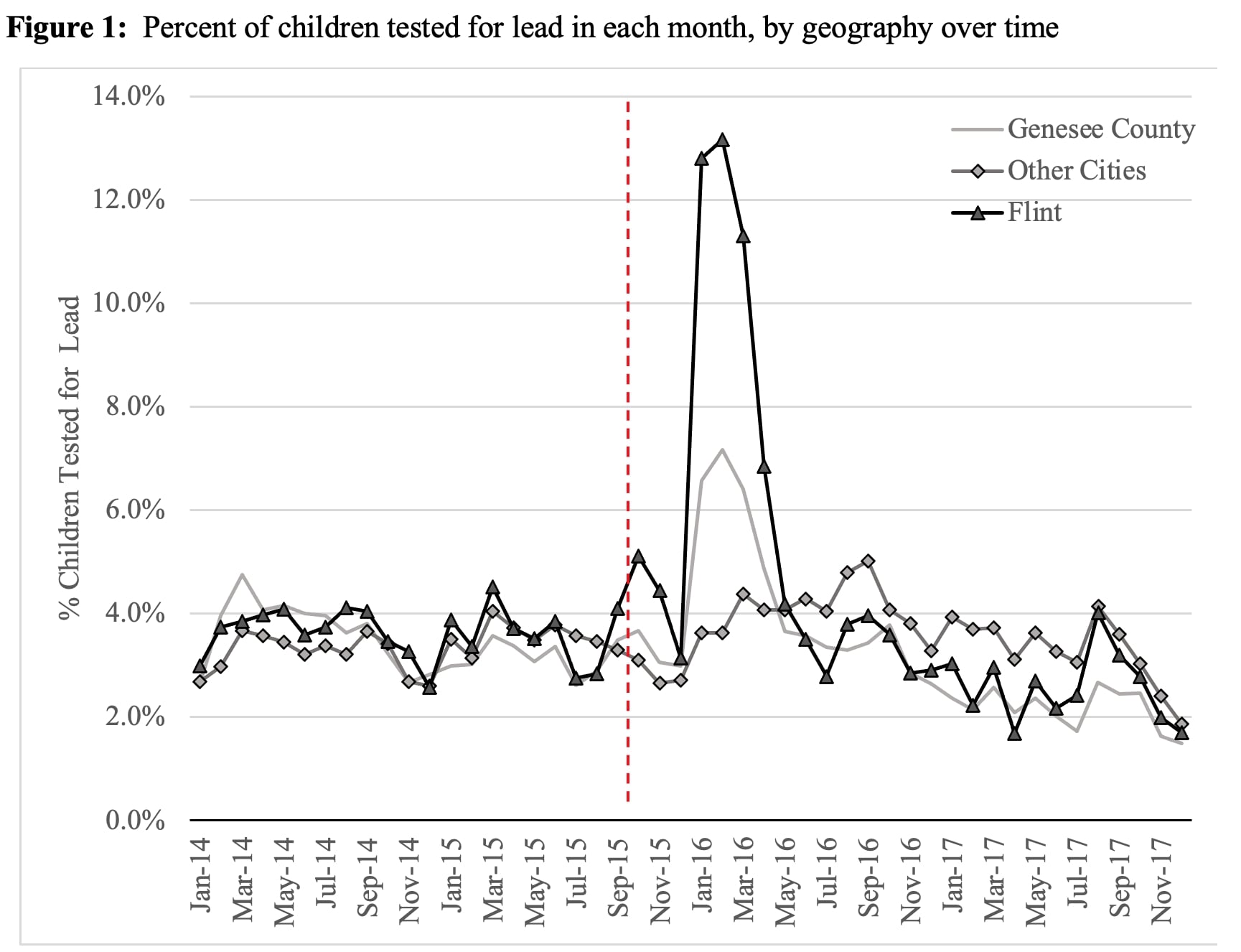

However, once news of the crisis broke, parents in Flint were galvanized into action. The percentage of children on Medicaid receiving a lead test in the months after September 2015 jumped from a baseline of about 3% to about 5% after the announcement by Flint officials, and to a high of about 13% when former Michigan Governor Rick Snyder declared a state of emergency in January 2016.

“What surprised us most was that these higher rates of testing did not persist after these announcements,” Slusky said. “It’s really hard to make long-term changes in behavior. All the changes we measure came from kids getting their first lead test earlier, and not kids getting a test who wouldn’t have otherwise received it.”

A KU faculty member since 2015, Slusky specializes in health economics and labor economics. He has written extensively on this current subject, including the pieces “Impacts of Lead Exposure on Health, Fertility and Education” and “The Impact of the Flint Water Crisis on Fertility.”

Is it inevitable that we will witness another lead-related crisis like the one in Flint?

“We already have,” Slusky said, citing Newark, New Jersey, in 2016 and Jackson, Mississippi, this year.

“While the $15 billion in the 2021 infrastructure bill to replace lead service lines will help, it is probably not enough to replace all the lines in the country. Nor will it address other sources of lead in the home such as traces of old lead paint," he said. “Focusing on prevention and mitigation of lead outbreaks can therefore make a big difference in reducing both the scale of future crises and the level of harm to exposed children.”

This story was originally published by the University of Kansas on November 3, 2022.