By Archana Pyati

Small business and intellectual property advocates pressed Congress to protect the Bayh-Dole Act (the federal law enshrining the rights of university researchers to patent and license their discoveries for commercial use) and reauthorize the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) federal grant programs, at a Capitol Hill panel on February 4.

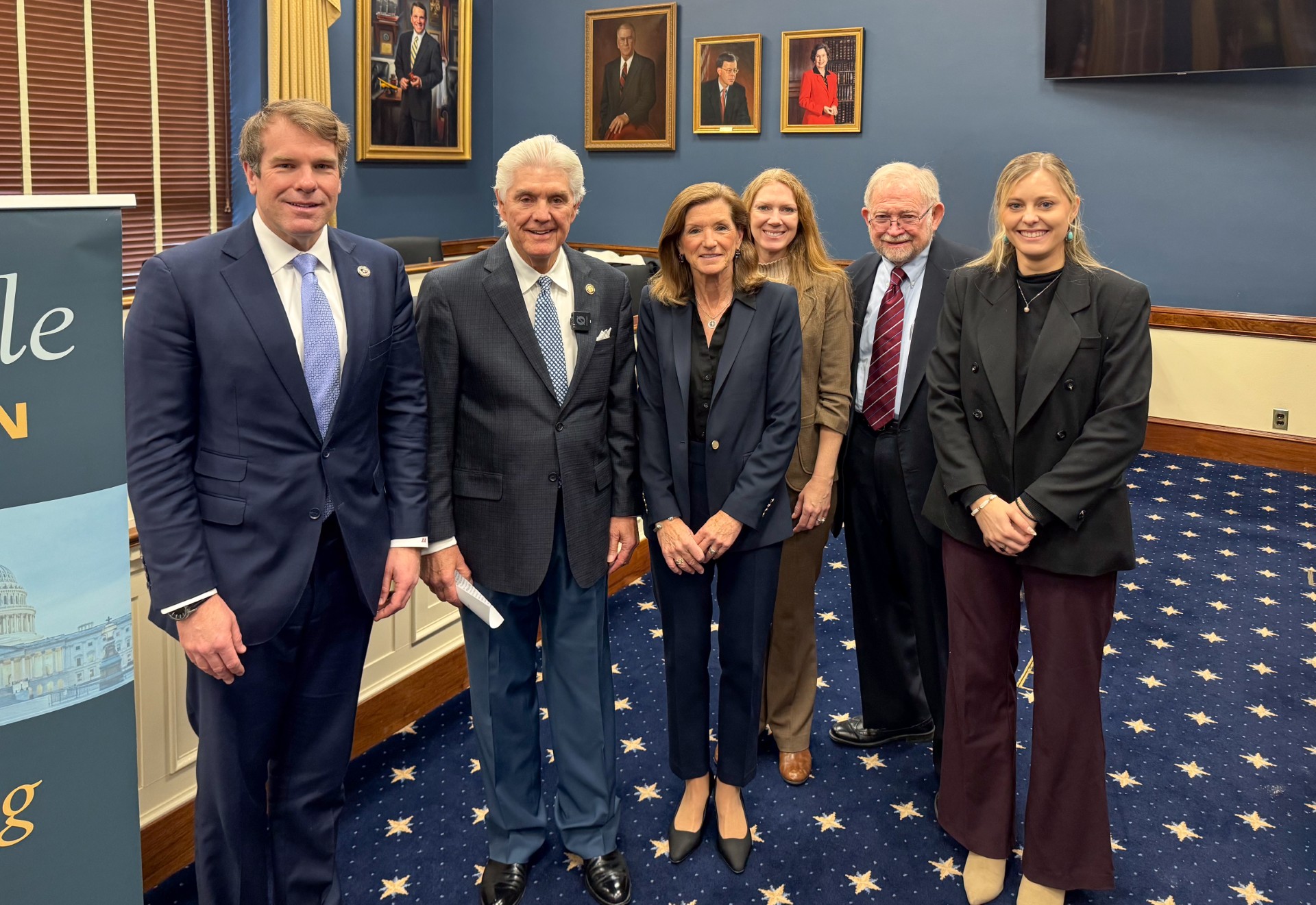

Passed with bipartisan support in 1980, the Bayh-Dole Act “started the greatest renaissance of technology in human history,” said moderator Joe Allen, executive director of the Bayh-Dole Coalition, which organized the event and of which AAU is a member. The event was hosted by Rep. Roger Williams (R-TX), chairman of the House Subcommittee on Small Business.

Prior to Bayh-Dole, the government retained patent ownership of the scientific research it funded but did not invest in additional resources to commercialize that research and develop products to benefit the public. Bayh-Dole’s passage unleashed the biotech revolution; hundreds of drugs, vaccines, and innovations – including mRNA technology – have been developed from patented discoveries licensed by startups and university spinoffs. Other innovations – such as Google’s search engine – would not have been possible without Bayh-Dole’s guarantee of patent rights to inventors.

Bayh-Dole and the SBIR/STTR programs work in tandem: the former establishes the legal framework that allows researchers to retain ownership of their patents, and the latter provides the seed funding for entrepreneurs to develop proof of concepts and invest in intensive R&D. (This is why the SBIR/STTR programs are also known as “America’s Seed Fund;” they award $4 billion in competitive grants to small businesses annually.)

“SBIR/STTR grants are often the bridge between research and commercialization,” explained Karen Kerrigan, president and chief executive officer of the Small Business and Entrepreneurship Council.

But both the Bayh-Dole Act and the SBIR/STTR programs currently face uncertainty. Funding for SBIR/STTR, which provides early-stage capital to bring innovative technologies to market, lapsed on September 30, 2025. And, due to a breakdown of negotiations in the Senate, the programs were not reauthorized by a temporary spending bill that reopened the government.

Moreover, despite longstanding bipartisan support behind the Bayh-Dole Act, a recent proposal by Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick to tax royalties that universities earn from patents by as much as 50% has alarmed stakeholders, including university leaders and researchers, technology transfer professionals, the small business community, and venture capitalists.

“Why mess with something that is a proven model?” said Kerrigan. “Bayh-Dole has been a proven model.” Panelists noted that efforts to undermine Bayh-Dole would disproportionately harm small business entrepreneurs, who are the driving force behind efforts to bring academic research into the marketplace in the form of new products and technologies. In fact, small businesses license about 70% of inventions from universities and federal research labs, said Allen, who shepherded Bayh-Dole through Congress as a staffer for former Sen. Birch Bayh (D-IN).

Small businesses and startups form the backbone of the U.S. innovation ecosystem, said William Briggs, the deputy administrator for the U.S. Small Business Administration (which oversees SBIR/STTR). Noting that the nation’s founders were themselves entrepreneurs, Briggs observed that “small business innovation is ingrained in our national culture and part of our strategic advantage of who we are as Americans.”

Also, firms with seed funding from SBIR/STTR are more successful in attracting follow-on venture capital. “SBIR/STTR are absolutely critical” in providing a signal to investors, said panelist Ashlyn Roberts, vice president of government affairs at the National Venture Capital Association. She noted that “companies are starting to feel the burn” from the lapsed funding.

Biotech firms that win SBIR/STTR awards have a strong track record. A 2022 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) report found they developed 12% of new drugs and 16% of “priority review” drugs from 1996 until 2020, said panelist Jere Glover, executive director of the Small Business Technology Council.

Another NASEM report on SBIR/STTR at the Department of Defense, the agency with the largest allocation for these awards, praised the programs for connecting the DOD with small businesses with “distinct capabilities.” The grants also have wide geographical distribution, helping to establish innovation clusters in rural and non-coastal states.

Noting the administration’s recent $12 billion investment in building a stockpile of critical minerals and its commitment to “onshoring” manufacturing to create domestic supply chains, Briggs touted the many SBA loan programs – including SBIR/STTR - that support entrepreneurs seeking to take advantage of this moment of industrial innovation. His office is working closely with Congress to reauthorize the grant programs.

It won’t be a moment too soon for panelist Jennifer Pagán, a scientist-entrepreneur who launched AquiSense, a North Carolina-based water disinfection company after winning an SBIR grant. Before AquiSense, she developed and licensed technology that used ultra-violet light to disinfect water as a doctoral researcher in electrical engineering at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

“What makes America a better place than any in the world to start a business and succeed with new technology is the combination of tools that are available,” said Pagán, now AquiSense’s chief technology officer. “These create a more favorable climate than any place in the world. Quite frankly this lapse is threatening that reputation, because SBIR/STTR is a critical leg that has been yanked out from the stool.”

Archana Pyati is editorial and content officer at AAU.